Prof.

Bryan Caplan

bcaplan@gmu.edu

http://www.bcaplan.com

Advanced

Public Choice

Lecture 2: Voter Motivation, II:

Ideological and Other Voting

I.

Factor Analysis

A.

One statistical technique social scientists outside of economics use a

great deal is factor analysis.

B.

The main idea of factor analysis: reducing a lot of variables to a

smaller number of "summary" variables, aka "factors" or

"dimensions."

C.

The classic example: intelligence testing. A test has 100 items. Is it possible to extract a smaller

number of summary variables?

D.

Yes. In fact, factor

analysis on variables related to cognitive ability normally finds ONE

over-riding factor (called g for "general intelligence"). Cognitive ability is essentially

"one-dimensional."

E.

Performance on individual test items can be seen as a function of g

plus noise. The greater the

predictive power of g, the higher we say the item's g-loading is.

1.

Ex: Analogies have a higher g-loading than pure memory tasks.

F.

Factor analysis in no way guarantees the existence of a single over-riding

factor. For example, on personality

tests, factor analysis normally extracts FIVE unrelated factors.

G.

Factors do not label themselves.

Ordinary language terms are convenient, though occasionally misleading.

1.

Ex: OCEAN

H.

On purely random data, no factors would emerge.

II.

The Dimensionality of

A.

There are many different ways to analyze political beliefs.

1.

Libertarian-statist spectrum

2.

Christian-secular spectrum

B.

What can factor analysis tell us about the dimensionality of

C.

Strong result: As with intelligence, empirical tests typically find

that political opinion is roughly one dimensional.

D.

What is the dimension?

Empirically,

B.

On a deep level, this spectrum may not make a great deal of sense. Libertarians, for example, often argue

that there are really two dimensions - personal freedom and economic freedom:

1.

Libertarians - pro-personal, pro-economic

2.

Populists - anti-personal, anti-economic

3.

Liberals - pro-personal, anti-economic

4.

Conservatives - anti-personal, pro-economic

E.

But empirically, most people line up on the diagonal, and the other two

boxes are sparsely inhabited.

F.

G.

A second dimension (related to race) occasionally pops up, but is no

longer important. P&R's story:

During the 50's, otherwise liberal Southern Democrats often opposed civil

rights measures, and otherwise conservative Republicans often favored them. Once the Southern Democrats left the

party, and debate shifted from "equality of opportunity" to

"equality of result," position on further civil rights measures began

to correlate well with the rest of the liberal-conservative dimension.

H.

Similarly, Levitt and earlier researchers have found that

one-dimensional ideological measures of l-c like

I.

Less work has been done on the dimensionality of individual citizens'

opinions, but once again, a strong liberal-conservative dimension pops out of

the data.

J.

Remarkably, voting in the U.N. is also one-dimensional, in spite of the

extreme heterogeneity of the participants.

The dimension is something like "attitudes towards the

U.S./Israel."

III.

Ideological Voting

A.

As mentioned earlier, the main problem with the simple sociotropic

voting model is that it has trouble explaining disagreement.

B.

The empirical evidence on ideology suggests a more sophisticated

interpretation of sociotropic voting.

C.

Motivation is indeed sociotropic: People support the policies they

think are in the public interest.

D.

But: There are large ideological disagreements about the public

interest. Ideology determines

beliefs about what policies "work" and what counts as

"working."

E.

Ex: Affirmative action.

Conservatives and liberals argue about whether it works (are blacks

better-off because of it?), but also disagree about what it means to

"work" (a "level playing field" versus a "fair

outcome"?).

F.

Important theoretical point: If ideology is one-dimensional, and people

largely vote ideologically, then the simple MVT's seemingly strong assumptions are

satisfied. Perhaps the issue-space

only looks multi-dimensional.

V.

Ideology and Reduction

A.

Main objection to ideological voting model: Can't ideology be reduced

to personal interests?

B.

Ex: Isn't conservatism just the "ideology of the rich," and

liberalism the "ideology of the poor"?

C.

No. The correlation between

income and professed ideology is very low.

In the GSS, for example, the correlation between real income and

POLVIEWS (a 1-7 measure of left-right ideology) is .06.

D.

So what does determine ideology? Is it education?

E.

Once again, no. Education

and ideology are close to unrelated (r=-.03) when you look at a random sample of

Americans from the GSS (as opposed to, say, a 50/50 sample of random Americans

and university faculty!).

F.

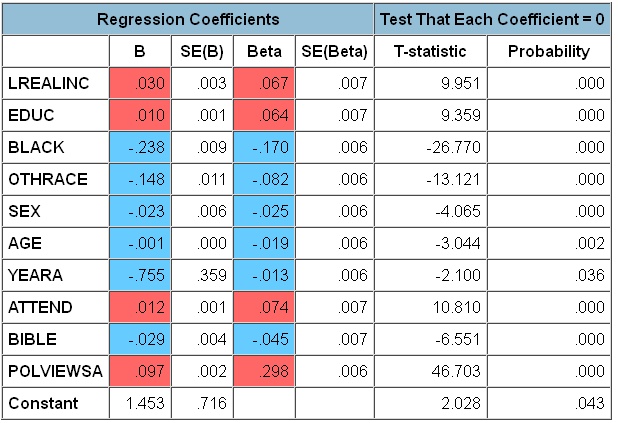

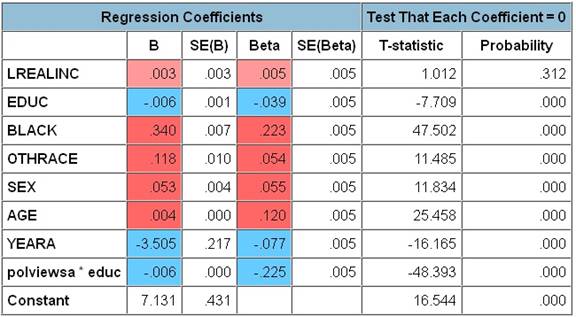

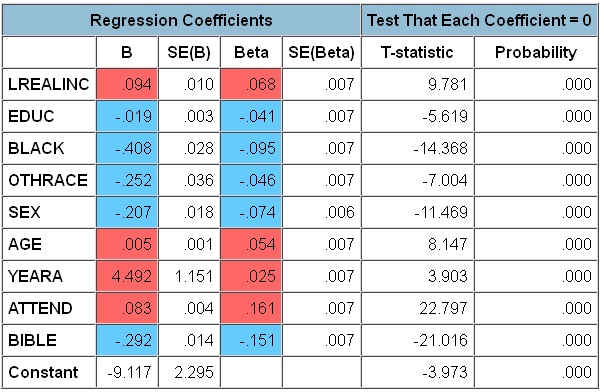

In a multiple regression framework, there is a tendency for income to

make people more conservative and education to make people more liberal. [Table 2]

G.

Both are clearly statistically significant, but the actual effect is

small. On a 6-point scale:

1.

Raising log of real income by 1 – a huge change - makes people

.096 units more conservative.

2.

Going from a high school degree to a BA makes people .084 units more

liberal.

H.

What then is ideology? As

far as anyone can show, ideology is an independent causal force. Ideology explains a great deal about

people's beliefs, but no standard social science variable does much to explain

ideology.

I.

Maybe someone will one day show that ideology reduces to something

else, but given the failure of all the obvious candidates, I doubt it. (But stay tuned for the genetics of

politics next week!)

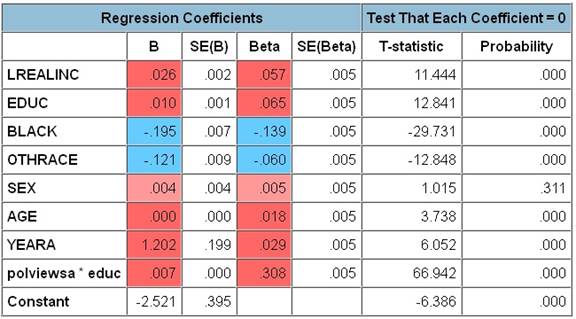

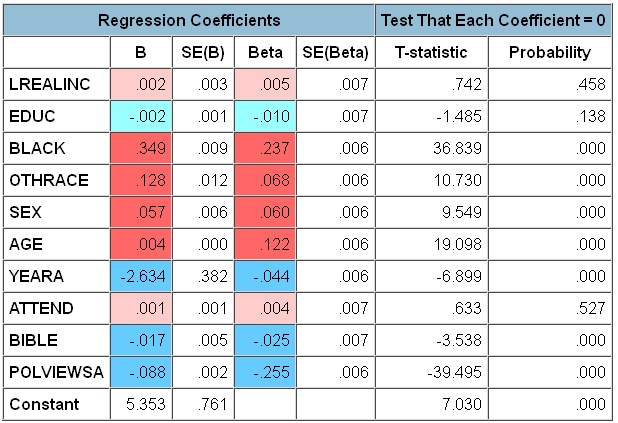

VI.

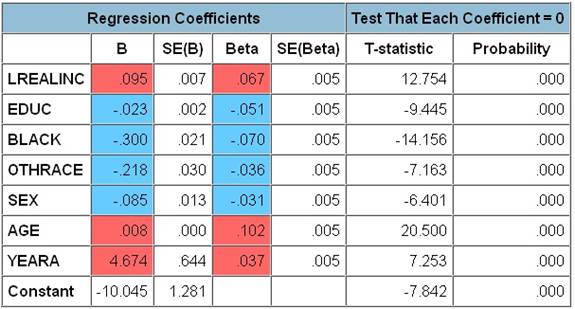

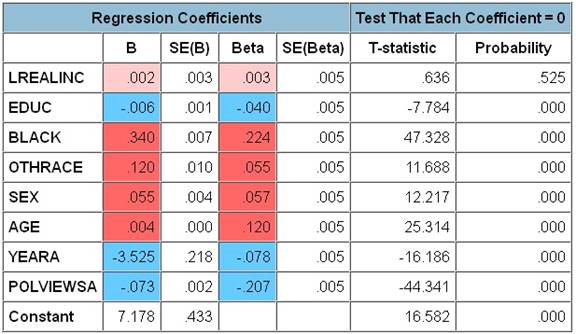

Case Study: The Determinants of Party Identification, II

A.

Question: Returning to last

week's linear probability model of party identification, what happens in the

GSS if you also control for stated ideology? N≈41,000,

so focus on magnitudes, not t-stats.

B.

[Tables 3a&3b]

C.

Answer: Ideology matters

even more than race. Moreover, the

slight change in the other coefficients shows that ideology is far from a

"mere proxy for self-interest."

D.

Consider two examples for 2010.

1.

Ex. #1: Black female with

$1M annual income in 1986 dollars, 30 years old, college graduate.

2.

Ex. #2: White male with

$10k annual income, 30 years old, high school education, conservative ideology.

E.

Ex. #1: [Since we don't

know ideology, use Tables 1a and 1b]

Estimated probability of being a Democrat: 56.4%; estimated probability

of being a Republican: 26.6%.

F.

Ex. #2: [Using Tables 3a

and 3b] Estimated probability of

being a Democrat: 6.8%; estimated probability of being a Republican: 59.1%. (Age coefficient to one more decimal

place=.0005).

VII.

Income, Education, Ideology, and Opinion

A.

For specific opinions (as opposed to party identification), income

empirically often seems to make a large difference.

1.

Ex: High income people seem much more in favor of immigration than low

income people.

B.

But

the effect of income almost always disappears once you control for education. Ph.D.s who drive cabs think like other

Ph.D.s, not other cab drivers.

C.

How does education affect opinion? More educated people tend to be

both more tolerant and more appreciative of free markets.

D.

Even though voting is one-dimensional, opinion looks

two-dimensional.

E.

Moreover, the two dimensions more or less fit the two-dimensional

personal freedom/economic freedom diagram.

Education shifts the diagonal up and to the right.

F.

This fact suggests that politicians might really compete over two

dimensions rather than one, again raising doubts about the median voter model.

G.

In practice, however, the liberal-conservative dimension appears to be

far more electorally salient.

Education affects issue beliefs, but appears to be independent of party

identification.

H.

Why? How come liberals

ally, but not high school drop-outs?

VIII.

Case Study: Economic Beliefs

A.

Now let us go through two illustrations from the SAEE: tendency to

blame economic difficulties on:

1.

Immigration

2.

"Excessive profits"

B.

If we do not control for education, income appears to have a large effect

on these beliefs. [Table 4a, 4b]

C.

Controlling for education, though, makes the apparent effect of income

almost disappear. [Table 5a, 5b]

D.

Immigration.

1.

Opposition shrinks as education rises.

2.

Opposition grows as conservatism rises.

E.

"Excessive profits."

1.

Assigning blame falls as education rises.

2.

Assigning blame falls as conservatism rises.

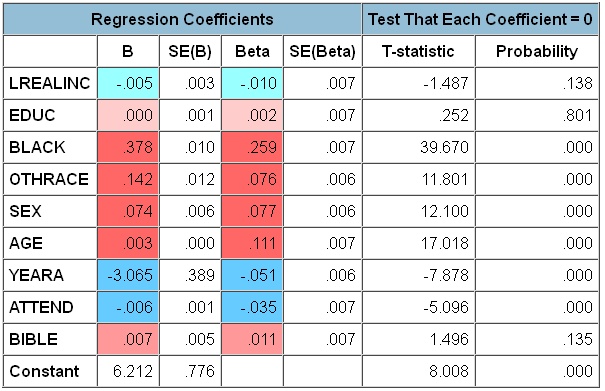

IX.

Religion, Party, and Ideology

A.

Many observers of modern American politics think that the divide

between secular and religious voters matters. Does it?

B.

The General Social Survey has measures of religious belief (especially

Biblical literalism) and religious practice (especially church

attendance). N≈26,000.

Bible goes from 1-4, 1 being most literalist; ATTEND goes from 1-7, 7

being most frequent.

C.

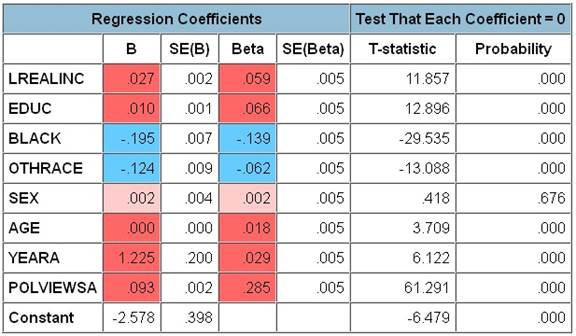

First,

let’s add these measures to the initial linear probability models from

Week 4. (Tables 8a&8b)

D.

Results: Both measures have substantial but not overwhelming predictive

power, especially for Republicans.

E.

What about religion and ideology?

Table 9 shows that our two religious measures are by far the strongest

predictors of ideology. If the

liberal-conservative divide is “really” something else, it’s

a secular-religious divide.

F.

Note, however, that the magnitudes are still not huge. The ideology variable goes from -3 to

+3, but moving from the minimum to the maximum on the religious variables only

makes you 1.32 units more conservative.

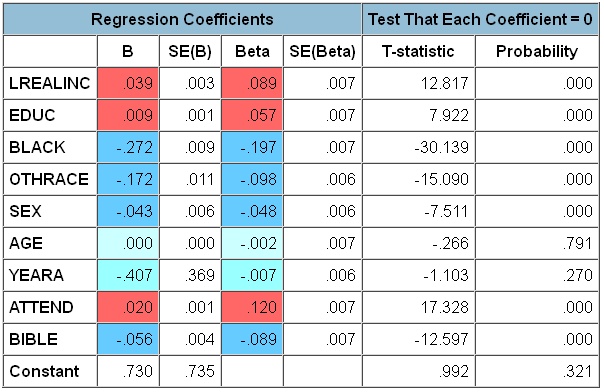

G.

What if we race ideology against religion as a determinant of party

identification? Ideology still

crushes religion, especially for P(Dem). (Tables 10a and 10b)

X.

Personality and Ideology

A.

The Five Factor Model now reigns supreme in personality

psychology. Acronym: OCEAN. (Myers-Briggs analogs in parenthesis).

1.

Openness to Experience (Intuitive vs. Sensing)

2.

Conscientiousness (Judging vs. Perceiving)

3.

Extraversion (Extraverted vs. Introverted)

4.

Agreeableness (Feeling vs. Thinking)

5.

Neuroticism (No MB analog, but the negative of Neuroticism is

Stability)

B.

Despite economists’ incredulity, personality measures are

predictively useful. Ex:

Occupational choice.

C.

Especially given the low MC of voting one way or another, it seems

plausible that personality would have large effects on political views. Do they?

D.

Data sets with personality and political info are scarce, but some

serious results are now in. Gerber

et al summarize past findings, and present some new ones.

E.

Robust past findings: Conservatives are lower in Openness and higher in

Conscientiousness. Lower Openness

and Higher Conscientiousness predict higher conservatism for almost all

measures; higher Stability predicts higher conservatism for most but not all

measures. (Table 4)

F.

Magnitudes in Gerber et al’s data: Personality variables go from

0-1, ideology goes from 1-5. So

going from the minimum to the maximum level of Openness makes people about a

point less conservative, and going from the minimum to the maximum level of

Conscientiousness makes people about half a point more conservative.

G.

Gerber et al distinguish economic and social ideology (scaled to have

mean=0 and SD=1) and find additional patterns, even controlling for education

and church attendance. (Table 6 and Figure 1)

H.

The robust predictors of social conservatism, like overall

conservatism, are Openness (-), and Conscientiousness (+).

I.

The robust predictors of economic conservatism are: Extraversion (+),

Agreeableness (-), Conscientiousness (+), Stability (+), and Openness (-). Free-marketeers are closed,

conscientious, disagreeable, emotionally stable extraverts.

J.

Interpretation? Two they consider, and one they

don’t:

1.

Some

personalities are less self-interested than others.

2.

Some

personalities have different interests than others.

3.

Some

personalities see the world more clearly than others.

K.

Compared to other

predictors of

ideology, these are strong. But in

absolute terms, ideology remains hard to predict.

XI.

Genes and Political Behavior

A.

Political attitudes and behavior often seem to run in families. Why is this?

B.

People usually assume it’s nurture, but in most families, there

is a confounding variable: genes.

C.

How can we distinguish the effects of nature and nurture? There are two standard “behavioral

genetic” approaches:

1.

Twin studies

2.

Adoption studies

D.

Adoption studies are still fairly unexplored for political attitudes

and behavior, but quite a few twin studies exist.

E.

Main findings: Nurture matters a lot for party identification.

F.

However, genes account for most or all of the family resemblance in:

1.

Whether you vote

2.

Whether you always vote for one party

3.

Issue positions (and a wide range have been studied!)

4.

Left-right ideology

G.

There are strong parallels between the behavior genetic results for

religion and politics. Religious affiliation is strongly influenced by

parents, but by mid-adulthood, genes explain most or all familiar resemblance

in:

1.

Church attendance

2.

Religious intensity (how religious you feel, how interested you are)

3.

Doctrinal views

XII.

Does Policy Match Public Opinion?

What Are the Unpopular Policies?

A.

Now that we have a better grip on voter motivation, let us return to

the earlier question: Is the median voter model correct?

B.

It is hard to do formal empirical tests on the federal government

(without internationally comparable data, N=1). But there is a lot of informal evidence

that the median voter gets what he wants.

C.

What does the federal government do? Is this what the median voter

wants? (http://www.cbo.gov/budget/data/historical.pdf)

1.

Spending (2015)

|

Source |

Share |

|

Social

Security |

23.9% |

|

Defense |

15.8% |

|

Domestic

Discretionary |

15.8% |

|

Medicare |

17.2% |

|

Net

Interest |

6.1% |

|

Income

Security |

8.2% |

|

Medicaid |

9.5% |

|

Other

Retirement/Disability |

4.4% |

|

Other |

6.1% |

|

Offsetting

receipts |

-7.0% |

2.

Taxes (2015)

|

Source |

Share |

|

Individual

Income Taxes |

47.4% |

|

Payroll

Taxes |

32.8% |

|

Corporate

Income Taxes |

10.6% |

|

Excise

Taxes/Customs |

4.1% |

|

Other |

5.1% |

3.

A lot of regulation: Environmental, worker safety, drug safety,

anti-competitive behavior, labor...

D.

Starting with the budget: Social Security and Medicare remain extremely

popular programs; the military is also usually well-regarded. The remaining items are more

contentious.

E.

Broadly defining "welfare" as Medicaid and Income Security,

we get 17.7% of the budget. But:

1.

Few people want to actually abolish these programs

2.

Medicaid also pays for middle-class nursing home residents who have

depleted their personal savings.

F.

The national debt is unpopular, but repudiating it would be even less

popular. So "net

interest" ultimately has voter support.

G.

That leaves 22% of the budget for "domestic discretionary"

and "other" spending.

Some of this spending is "waste.” Waste is unpopular. But outside of isolated examples of $500

toilet seats, what spending do a majority of Americans agree is wasteful?

H.

Turning to spending: It is surprising that income and SS taxes are such

a large percentage of the budget.

But insofar as business "passes on" corporate and other taxes,

do a majority of Americans really want significant changes here?

I.

Regulation is more complicated.

Are there majorities in favor of weaker (or stronger) environmental regulation? Worker safety? Drugs?

J.

Challenge: What

policies exist that a majority of American voters oppose? Consider all the clichés of

politics. Do any hold water?

1.

Relatively weak

gun control?

2.

Foreign aid?

3.

NAFTA?

XIII.

Bartels’

Case that Government Is Too Small

A.

In the

GSS, the median voter wants to spend

more in most areas. The only area

where the median voter consistently favors cuts is foreign aid.

B.

Larry

Bartels generalizes this finding to all 23 of the countries he looked at:

“Citizens in every country in every year wanted additional government

spending on health, education, old age pensions, the environment, and law

enforcement.”

C.

Both the

GSS and Bartels’ data also show, however, that voters around the world

want less spending overall! “The distribution of responses to

this question is, if anything, even more skewed than for the questions in the

battery on spending for specific government programs. Averaging across

countries and years, about two-thirds of the respondents said they favored cuts

in government spending, many ‘strongly’; only 10% were

opposed.”

D.

It is

well-known that adding a warning about the connection between higher spending

and higher taxes depresses support for spending.

E.

GSS

spending preference data doesn’t have such a warning. Bartels’ data does, but it’s

weird: “Remember that if you say "much more," it might require

a tax increase to pay for it.”

Problems:

1. It suggests that moderate spending increases don't require higher taxes.

2. It fails to mention that spending cuts would reduce taxes.

F. When the GSS gives a binary choice between higher spending on “social programs like health care, social security, and unemployment benefits” or lower taxes, 60% want higher spending. But adding a status quo category would almost certainly show that the median person favors the status quo over change in either direction.

G. Overall: Since voters’ stated budgetary preferences are contradictory, it is hard to tell if they are “getting what they want.” But the contradictions are weaker for better questions, which generally show that the median voter favors the status quo.

Table

2: The Determinants of Ideology (POLVIEWS rescaled to go from -3 to +3)

Table

3a: Conditional Probability of Being a Democrat, with Ideology

Table

3b: Conditional Probability of Being a Republican, with Ideology

Table

4a: Effect of Income on Beliefs About Immigration, No Education Control

|

Dependent Variable: IMMIG |

|

||||

|

Method: Least Squares |

|

||||

|

Date: 10/23/01 Time: 13:02 |

|

||||

|

Sample(adjusted): 1 1510 IF ECON<1 |

|

||||

|

Included observations: 1362 after

adjusting endpoints |

|

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

|

C |

1.581155 |

0.176059 |

8.980843 |

0.0000 |

|

|

BLACK |

-0.141790 |

0.076408 |

-1.855686 |

0.0637 |

|

|

ASIAN |

-0.002224 |

0.092337 |

-0.024084 |

0.9808 |

|

|

OTHRACE |

-0.004465 |

0.090074 |

-0.049576 |

0.9605 |

|

|

AGE |

-0.009174 |

0.007457 |

-1.230223 |

0.2188 |

|

|

AGE^2 |

0.000139 |

7.59E-05 |

1.832582 |

0.0671 |

|

|

MALE |

-0.130501 |

0.042039 |

-3.104298 |

0.0019 |

|

|

IDEOLOGY*(1-OTHIDEOL) |

0.106427 |

0.023119 |

4.603419 |

0.0000 |

|

|

OTHIDEOL |

0.242322 |

0.150883 |

1.606028 |

0.1085 |

|

|

JOBWORRY |

0.049389 |

0.019877 |

2.484734 |

0.0131 |

|

|

YOURFAM5 |

-0.018488 |

0.033123 |

-0.558180 |

0.5768 |

|

|

YOURNEXT5 |

-0.037205 |

0.033983 |

-1.094799 |

0.2738 |

|

|

INCOME |

-0.041745 |

0.010383 |

-4.020541 |

0.0001 |

|

|

R-squared |

0.069468 |

Mean dependent var |

1.218796 |

|

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.061191 |

S.D. dependent var |

0.779419 |

|

|

|

S.E. of regression |

0.755196 |

Akaike info criterion |

2.285819 |

|

|

|

Sum squared resid |

769.3625 |

Schwarz criterion |

2.335612 |

||

|

Log likelihood |

-1543.643 |

F-statistic |

8.392399 |

||

|

Durbin-Watson stat |

2.049180 |

Prob(F-statistic) |

0.000000 |

||

Table

4b: Effect of Income on Beliefs About “Excessive Profits,” No

Education Control

|

Dependent Variable: PROFHIGH |

||||

|

Method: Least Squares |

||||

|

Date: 10/23/01 Time: 13:02 |

||||

|

Sample(adjusted): 1 1510 IF ECON<1 |

||||

|

Included observations: 1355 after

adjusting endpoints |

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

C |

1.346526 |

0.164472 |

8.186947 |

0.0000 |

|

BLACK |

0.078105 |

0.071559 |

1.091486 |

0.2753 |

|

ASIAN |

-0.011367 |

0.087285 |

-0.130229 |

0.8964 |

|

OTHRACE |

0.160538 |

0.085611 |

1.875199 |

0.0610 |

|

AGE |

0.010419 |

0.006962 |

1.496472 |

0.1348 |

|

AGE^2 |

-7.23E-05 |

7.09E-05 |

-1.020087 |

0.3079 |

|

MALE |

-0.202624 |

0.039320 |

-5.153159 |

0.0000 |

|

IDEOLOGY*(1-OTHIDEOL) |

-0.090241 |

0.021657 |

-4.166787 |

0.0000 |

|

OTHIDEOL |

0.180299 |

0.140710 |

1.281355 |

0.2003 |

|

JOBWORRY |

0.037830 |

0.018623 |

2.031381 |

0.0424 |

|

YOURFAM5 |

-0.056647 |

0.030934 |

-1.831217 |

0.0673 |

|

YOURNEXT5 |

-0.104313 |

0.031768 |

-3.283568 |

0.0011 |

|

INCOME |

-0.036220 |

0.009713 |

-3.729038 |

0.0002 |

|

R-squared |

0.108802 |

Mean dependent var |

1.272325 |

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.100833 |

S.D. dependent var |

0.742522 |

|

|

S.E. of regression |

0.704092 |

Akaike info criterion |

2.145732 |

|

|

Sum squared resid |

665.2902 |

Schwarz criterion |

2.195732 |

|

|

Log likelihood |

-1440.733 |

F-statistic |

13.65318 |

|

|

Durbin-Watson stat |

2.008430 |

Prob(F-statistic) |

0.000000 |

|

Table

5a: Effect of Income on Beliefs About Immigration, Education Control

|

Dependent Variable: IMMIG |

||||

|

Method: Least Squares |

||||

|

Date: 10/23/01 Time: 12:49 |

||||

|

Sample(adjusted): 1 1510 IF ECON<1 |

||||

|

Included observations: 1362 after

adjusting endpoints |

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

C |

1.883690 |

0.174664 |

10.78466 |

0.0000 |

|

BLACK |

-0.174951 |

0.074420 |

-2.350864 |

0.0189 |

|

ASIAN |

0.035971 |

0.089924 |

0.400013 |

0.6892 |

|

OTHRACE |

-0.032613 |

0.087676 |

-0.371975 |

0.7100 |

|

AGE |

-0.004571 |

0.007273 |

-0.628464 |

0.5298 |

|

AGE^2 |

8.37E-05 |

7.41E-05 |

1.129602 |

0.2588 |

|

MALE |

-0.115403 |

0.040928 |

-2.819625 |

0.0049 |

|

IDEOLOGY*(1-OTHIDEOL) |

0.088741 |

0.022578 |

3.930411 |

0.0001 |

|

OTHIDEOL |

0.253523 |

0.146774 |

1.727304 |

0.0843 |

|

JOBWORRY |

0.036076 |

0.019394 |

1.860182 |

0.0631 |

|

YOURFAM5 |

0.004961 |

0.032329 |

0.153453 |

0.8781 |

|

YOURNEXT5 |

-0.025312 |

0.033084 |

-0.765072 |

0.4444 |

|

INCOME |

-0.011501 |

0.010667 |

-1.078253 |

0.2811 |

|

EDUCATION |

-0.121877 |

0.013828 |

-8.814086 |

0.0000 |

|

R-squared |

0.120175 |

Mean dependent var |

1.218796 |

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.111690 |

S.D. dependent var |

0.779419 |

|

|

S.E. of regression |

0.734604 |

Akaike info criterion |

2.231255 |

|

|

Sum squared resid |

727.4387 |

Schwarz criterion |

2.284878 |

|

|

Log likelihood |

-1505.485 |

F-statistic |

14.16323 |

|

|

Durbin-Watson stat |

2.020208 |

Prob(F-statistic) |

0.000000 |

|

Table

5b: Effect of Income on Beliefs About “Excessive Profits,”

Education Control

|

Dependent Variable: PROFHIGH |

||||

|

Method: Least Squares |

||||

|

Date: 10/23/01 Time: 12:49 |

||||

|

Sample(adjusted): 1 1510 IF ECON<1 |

||||

|

Included observations: 1355 after

adjusting endpoints |

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

C |

1.509230 |

0.166386 |

9.070651 |

0.0000 |

|

BLACK |

0.060476 |

0.071038 |

0.851317 |

0.3947 |

|

ASIAN |

0.008011 |

0.086629 |

0.092480 |

0.9263 |

|

OTHRACE |

0.144138 |

0.084945 |

1.696828 |

0.0900 |

|

AGE |

0.012815 |

0.006920 |

1.851821 |

0.0643 |

|

AGE^2 |

-0.000101 |

7.05E-05 |

-1.432204 |

0.1523 |

|

MALE |

-0.194440 |

0.039020 |

-4.983073 |

0.0000 |

|

IDEOLOGY*(1-OTHIDEOL) |

-0.099322 |

0.021551 |

-4.608611 |

0.0000 |

|

OTHIDEOL |

0.185962 |

0.139513 |

1.332934 |

0.1828 |

|

JOBWORRY |

0.030960 |

0.018516 |

1.672024 |

0.0948 |

|

YOURFAM5 |

-0.044179 |

0.030774 |

-1.435562 |

0.1514 |

|

YOURNEXT5 |

-0.097896 |

0.031524 |

-3.105476 |

0.0019 |

|

INCOME |

-0.020394 |

0.010153 |

-2.008678 |

0.0448 |

|

EDUCATION |

-0.064849 |

0.013178 |

-4.920943 |

0.0000 |

|

R-squared |

0.124610 |

Mean dependent var |

1.272325 |

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.116123 |

S.D. dependent var |

0.742522 |

|

|

S.E. of regression |

0.698080 |

Akaike info criterion |

2.129311 |

|

|

Sum squared resid |

653.4895 |

Schwarz criterion |

2.183157 |

|

|

Log likelihood |

-1428.608 |

F-statistic |

14.68370 |

|

|

Durbin-Watson stat |

2.000165 |

Prob(F-statistic) |

0.000000 |

|

Table

6a: Conditional Probability of Being a Democrat, with Ideology*Educ

Table

6b: Conditional Probability of Being a Republican, with Ideology*Educ

Table

7a: Effect of Income on Beliefs About Immigration, Ideology*Educ Interaction

|

Dependent Variable: IMMIG |

||||

|

Method: Least Squares |

||||

|

Date: 10/23/01 Time: 12:54 |

||||

|

Sample(adjusted): 1 1510 IF ECON<1 |

||||

|

Included observations: 1362 after

adjusting endpoints |

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

C |

1.901975 |

0.174285 |

10.91305 |

0.0000 |

|

BLACK |

-0.167020 |

0.074339 |

-2.246730 |

0.0248 |

|

ASIAN |

0.038885 |

0.089935 |

0.432370 |

0.6655 |

|

OTHRACE |

-0.032774 |

0.087630 |

-0.374001 |

0.7085 |

|

AGE |

-0.004735 |

0.007263 |

-0.651871 |

0.5146 |

|

AGE^2 |

8.50E-05 |

7.40E-05 |

1.148399 |

0.2510 |

|

MALE |

-0.116930 |

0.040887 |

-2.859876 |

0.0043 |

|

IDEOLOGY*(1-OTHIDEOL)*EDUCATION |

0.020108 |

0.004718 |

4.261634 |

0.0000 |

|

OTHIDEOL*EDUCATION |

0.062666 |

0.032606 |

1.921896 |

0.0548 |

|

JOBWORRY |

0.036512 |

0.019397 |

1.882333 |

0.0600 |

|

YOURFAM5 |

0.005987 |

0.032285 |

0.185437 |

0.8529 |

|

YOURNEXT5 |

-0.025103 |

0.033047 |

-0.759605 |

0.4476 |

|

INCOME |

-0.011887 |

0.010661 |

-1.114952 |

0.2651 |

|

EDUCATION |

-0.124634 |

0.013817 |

-9.020040 |

0.0000 |

|

R-squared |

0.122481 |

Mean dependent var |

1.218796 |

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.114018 |

S.D. dependent var |

0.779419 |

|

|

S.E. of regression |

0.733641 |

Akaike info criterion |

2.228631 |

|

|

Sum squared resid |

725.5321 |

Schwarz criterion |

2.282253 |

|

|

Log likelihood |

-1503.698 |

F-statistic |

14.47294 |

|

|

Durbin-Watson stat |

2.021390 |

Prob(F-statistic) |

0.000000 |

|

Table

7b: Effect of Income on Beliefs About “Excessive Profits,”

Ideology*Educ Interaction

|

Dependent Variable: PROFHIGH |

||||

|

Method: Least Squares |

||||

|

Date: 10/23/01 Time: 12:54 |

||||

|

Sample(adjusted): 1 1510 IF ECON<1 |

||||

|

Included observations: 1355 after

adjusting endpoints |

||||

|

Variable |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

t-Statistic |

Prob. |

|

C |

1.504577 |

0.166017 |

9.062768 |

0.0000 |

|

BLACK |

0.048497 |

0.070958 |

0.683463 |

0.4944 |

|

ASIAN |

-0.004565 |

0.086640 |

-0.052685 |

0.9580 |

|

OTHRACE |

0.135789 |

0.084901 |

1.599375 |

0.1100 |

|

AGE |

0.013030 |

0.006910 |

1.885486 |

0.0596 |

|

AGE^2 |

-0.000104 |

7.04E-05 |

-1.471935 |

0.1413 |

|

MALE |

-0.192414 |

0.038981 |

-4.936041 |

0.0000 |

|

IDEOLOGY*(1-OTHIDEOL)*EDUCATION |

-0.022115 |

0.004490 |

-4.924966 |

0.0000 |

|

OTHIDEOL*EDUCATION |

0.049965 |

0.030994 |

1.612075 |

0.1072 |

|

JOBWORRY |

0.028983 |

0.018517 |

1.565193 |

0.1178 |

|

YOURFAM5 |

-0.046264 |

0.030730 |

-1.505501 |

0.1324 |

|

YOURNEXT5 |

-0.096444 |

0.031489 |

-3.062790 |

0.0022 |

|

INCOME |

-0.019645 |

0.010146 |

-1.936233 |

0.0530 |

|

EDUCATION |

-0.065029 |

0.013171 |

-4.937448 |

0.0000 |

|

R-squared |

0.126969 |

Mean dependent var |

1.272325 |

|

|

Adjusted R-squared |

0.118506 |

S.D. dependent var |

0.742522 |

|

|

S.E. of regression |

0.697138 |

Akaike info criterion |

2.126612 |

|

|

Sum squared resid |

651.7280 |

Schwarz criterion |

2.180458 |

|

|

Log likelihood |

-1426.780 |

F-statistic |

15.00220 |

|

|

Durbin-Watson stat |

2.001392 |

Prob(F-statistic) |

0.000000 |

|

Table

8a: Conditional Probability of Being a Democrat, with Literalism and Attendance

Table

8b: Conditional Probability of Being a Republican, with Literalism and

Attendance

Table 9: Determinants of Ideology, with Literalism and

Attendance

Table

10a: Conditional Probability of Being a Democrat, with Ideology and Religion

Table

10b: Conditional Probability of Being a Republican, with Ideology and Religion