Prof.

Bryan Caplan

bcaplan@gmu.edu

http://www.bcaplan.com

Econ

854

I.

The Stationary Bandit Model

A.

In the minds of many, the only alternative to

democracy is dictatorship.

B.

Tullock’s Question - “What’s

so bad about dictatorship anyway?” – highlights the fact that

public choice economists have spent little energy analyzing history’s typical form of government.

C.

Simplest approach: Dictatorship is equivalent to

democracy with a single - and perfectly decisive - voter.

D.

All of the usual rules about democracy that

hinge on low probability of decisiveness reverse:

1.

Self-interest

2.

Instrumentalism

3.

Rationality

E.

Thus, we should expect dictators to be highly

self-interested, but more interested in rationally assessing policies' actual

consequences.

F.

Will this lead to bad consequences for the

dictators’ subjects?

According to McGuire and Olson’s “stationary bandit

model,” not necessarily. As

long as the dictator knows that he will be around for a long time, it is in his

rational self-interest to encourage/allow economic development – to take

a smaller slice of the pie in order to make it grow faster.

1.

Alternate perspective: Stationary bandits go to

the maximum of the long-run Laffer

curve instead of the short-run or instantaneous Laffer curve.

G.

Remember the Tiebout model? It is basically a model of dictatorship

constrained by mobile capital and labor, and under standard assumptions it

yields perfectly competitive results.

1.

If the rulers of Tiebout governments were really

dictators, then my arguments about non-profit competition would no longer

apply.

H.

In the real world, dictators often respond to

the mobility of capital and labor by trying to make them less mobile. The Berlin Wall is the most notorious

– but not the most horrific – example.

1.

However, dictators do treat mobile resources

better. East Germany rarely forced

tourists to become citizens, and Communist governments rarely defaulted on

their sovereign debt.

I.

Many dictators go further by making war to get

more resources under their control.

Why grow when you can conquer?

J.

Another reason for dictators to stifle growth:

Growth leads to contact with the outside world and/or free thought, which tends

to undermine the dictator’s authority.

II.

Constrained Dictatorship and the Paradox of

Revolution

A.

Very few dictatorships actually fit the

“one decisive voter” model, though modern totalitarian regimes

– like Stalin’s USSR, the Kims’ North Korea, and the last

years of Hitler’s Germany – come close.

B.

Almost all dictatorships throughout history have

instead been “authoritarian.”

The dictator has a lot of say, but at least de facto, so do many other

actors. The dictator ignores them

at his own risk; if he goes over the line, he risks a coup.

C.

Most people add that at some point, an abusive

dictator would provoke popular resistance.

D.

Mises argues that this threat is so strong that

dictatorships follow exactly the same policies that democracies would

have! I call this his

“Democracy-Dictatorship Equivalence Theorem.”

E.

Tullock, in contrast, argues that collective

action problems make popular revolutions virtually impossible.

F.

Most political observers believe in the

existence of revolutions, so for them Tullock’s argument creates a

“paradox of revolution” – revolutions seem impossible in

theory, yet they occur.

G.

For Tullock, however, “popular”

revolutions are thinly disguised battles between rival elites. The competing sides solve their

collective action problems with selective incentives – better ration

cards, promises of post-revolutionary jobs, etc.

H.

Trotsky’s on Tullock’s side: "An army cannot be built without

reprisals. Masses of men cannot be led to death unless the army command has the

death penalty in its arsenal. So

long as those malicious tailless apes that are so proud of their technical

achievements - the animals that we call men - will build armies and wage wars,

the command will always be obliged to place the soldiers between the possible

death in the front and the probable one in the rear."

I.

Watered down version of Tullock: Revolutionary

movements require true believers to get off the ground, but further growth

requires selective incentives.

III.

The Sociopathic Bandit Model?

A.

A major complication for economic models of

dictatorship: Being dictator effectively makes someone extraordinarily

wealthy. The resources of an entire

nation are theirs to command.

B.

Due to their extreme wealth, they may consume a

lot of altruism, expressive considerations, and/or irrationality despite their high price.

C.

Hence we see all sorts of strange behavior from

dictators:

1.

Mass murder of seemingly useful subjects.

2.

Awe-inspiring parades, monuments, palaces, etc.

3.

Bizarre social experiments.

4.

And… voluntary reduction to figurehead

status!

D.

Modern dictators rarely accept figurehead status,

but it happened all over 19th-century Europe when traditional monarchs

allowed and even urged a move to “constitutional monarchy.”

1.

Tullock’s explanation: The selective

pressure for power-hunger is much weaker in hereditary dictatorships.

E.

On balance, then, it is hard to make definite

statements about the selfishness, instrumentalism, or rationality of

dictatorial versus democratic policy.

It’s got to be studied empirically.

F.

The most convincing claim economic theory has to

make about dictatorship: It's a big gamble. Everything depends on the idiosyncrasies

of the Leader. This makes sense in

theory, and works empirically:

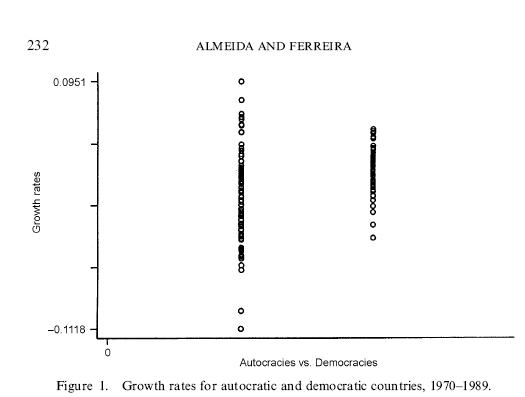

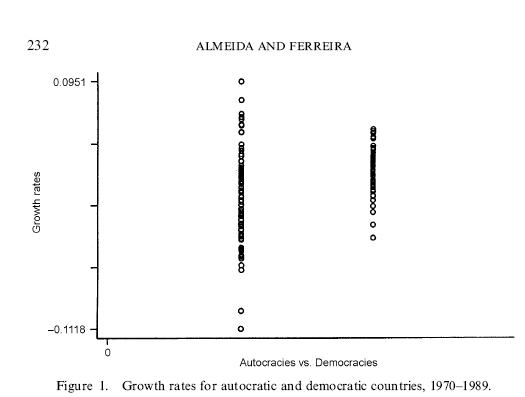

G.

Interesting finding #1: Average growth of

dictatorships and democracies is the same, but dictatorships have more

dispersion. Graph from Almeida and

Ferreira (2002):

H.

Interesting finding #2: When a dictator accidentally dies, growth rates

persistently change. When a

democratic leader accidentally dies, in contrast, they don’t.

IV.

Totalitarianism

A.

Political scientists distinguish between

“totalitarian” and “authoritarian” dictatorships. Standard totalitarian checklist courtesy

of Richard Pipes:

1.

official all-embracing ideology

2.

a single party of the elect headed by a

“leader” and dominating the state

3.

police

terror

4.

the ruling party's control of the means of

communication and the armed forces

5.

central command of the economy

B.

Since #5 is equivalent to socialism in the

traditional sense of the word, many socialists object to this criterion. But it is hard to rebut Trotsky’s

explanation: "In a country where the sole employer is the State,

opposition means death by slow starvation. The old principle: who does not work

shall not eat, has been replaced by a new one: who does not obey shall not

eat."

C.

One cheer for democracy: Totalitarianism has

almost never been established democratically. (Semi-convincing counter-example:

Hitler’s Germany). It arises

through civil war (USSR, China, etc.) or conquest (Eastern Europe, North

Korea).

D.

A few analytical narratives on the rise of

totalitarianism.

E.

A few analytical narratives on the implosion of

totalitarianism.

V.

Is Totalitarianism Possible? Economic Calculation Reconsidered

A.

Austrian economists were harsh critics of

totalitarianism before it existed. So

was everyone sensible. The uniquely

Austrian objection was that Characteristic #5 (socialism) is

“impossible.”

B.

Why is socialism impossible? Mises’ original argument:

1.

Economic calculation (comparing the cost of

different ways of doing the same thing) requires prices.

2.

Prices require some kind of market (not

necessarily laissez-faire).

3.

Under socialism, there is no market, therefore

no prices, therefore no calculation.

4.

Conclusion:

Socialism is impossible.

5.

Note:

For Mises, “impossible” means total social collapse! “[T]he

attempt to reform the world socialistically might destroy civilization. It would never set up a successful

socialist community.”

“Socialism cannot be realized because it is beyond human power to

establish it as a social system.”

C.

Many

socialists replied that market socialism or faster computers would make

socialism possible, but the rejoinders are obvious.

D.

My complaint: The argument is fine until the

conclusion! The lack of economic

calculation makes socialism more difficult,

but difficult is not impossible.

E.

Furthermore, the economic history of socialism

shows that:

1.

Its biggest disasters – massive famines

where millions died – were

caused by bad incentives, not lack of calculation.

2.

Socialist planners habitually ignored capitalist prices; they

didn’t just preserve socialism by free riding on the price system of the non-socialist

world.

3.

When socialist societies wanted results, they

used strong incentives and got results.

See their secret police, border security, militaries, space programs,

Olympic teams, and nuclear weapons.

F.

Also note: Incentive experiments in Soviet

agriculture showed that it was possible to sharply raise output, but the

experiments were ignored and their initiators punished.

VI.

Democratic Transitions: What Happens?

A.

One fact that Mises’ Equivalence Theorem

can explain, and Tullock can’t: When dictatorships peacefully become

democracies, policy usually doesn’t change that much. Examples:

1.

Strong populist back-lash against free-market

policies – and election of ex-Communists (and even unrepentant

Communists) – in the former Soviet bloc.

2.

Chile kept most of Pinochet’s economic

policies after he relinquished power.

3.

Free elections in Palestine did not lead to

dovish victory.

B.

However, there are many more plausible

explanations than Mises’ story that dictators are fully constrained by

the threat of revolution.

C.

The stationary bandit model. Stable dictators, like the median voter,

benefit if their country has pro-growth policies.

1.

Of course, this model isn’t very

convincing if you think that both kinds of governments have deeply inefficient

policies!

D.

Shared preferences. Especially in long-lasting dictatorships,

the dictator and the median voter come from the same basic political culture

and therefore have similar preferences.

E.

Status

quo bias. To a large extent,

dictatorships successfully brainwash their populations to think that what is,

is a pretty good idea.

1.

Fascinating

result: Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln

(2005) find that East Germans are markedly more

anti-market than West Germans, even controlling for income. Living under socialist tyranny

doesn’t make people hate socialism.