Prof. Bryan Caplan

bcaplan@gmu.edu

http://www.bcaplan.com

Econ 854

Week 4: Voter Motivation, I: Selfish, Group, and Sociotropic Voting

I.

Is the Median Voter Model Correct?

A.

In order to determine whether or not the median voter model is correct,

we must first find out "What voters want."

B.

Once we know what voters want, we can see whether actual policy

conforms to the policy preferences of the median voter.

C.

Probably the most popular account of voter motivation is that voters

are essentially self-interested.

D.

Economists typically think this, but so do many political scientists,

journalists, and "men in the street."

E.

Example #1: "Rich people vote Republican, and poor people vote

Democratic, because Republicans favor lower taxes and lower spending on

redistribution than Democrats."

F.

Example #2: "Blacks were treated worse under Jim Crow because they

weren't allowed to vote.

Politicians didn't worry about losing their votes for racist

policies."

G.

Example #3: "People

opposed to conservation laws must own stock in the timber industry."

II.

Defining the Self-Interested Voter Hypothesis (SIVH)

A.

There is a danger of tautology here: Is all behavior

"self-interested" by definition?

Was Mother Theresa self-interested?

B.

Throughout this course, I will only use the term

"self-interest" in the falsifiable, ordinary language sense of directly valuing only one's own material well-being, health, safety,

comfort, and so on. Two provisos:

1.

I interpret "people are self-interested" as "on average,

people are at least 95% selfish," not "all people are 100%

selfish."

2.

Drawing on evolutionary psychology, I interpret altruism towards blood

relatives in proportion to shared genes as self-interest.

C.

The self-interested voter hypothesis (SIVH) can then be defined as the

hypothesis that political beliefs and

actions of ordinary citizens are self-interested in the preceding sense.

III.

The Meltzer-Richards Model

A. A simple formal model the captures the standard implications of the SIVH is Meltzer and Richards’ "A Rational Theory of the Size of Government.”

B. Basic assumptions of M&R:

1. Proportional taxes

2. Flat welfare payment goes to everyone (as in a negative income tax)

3. Taxes and welfare affect behavior in standard ways

4. Everyone votes for the candidate that promises them the highest net income

5. Standard MVT holds

C. Implications: Politics is constrained class struggle. There is a battle between rich and poor. But even the poor do not want full equality because this would make them poorer too by eliminating all incentives.

1. Similarly, even the rich may want some redistribution to keep crime down, prevent revolution, etc.

D. For example, in the M&R model, Bill Gates would want a low tax rate, because he pays a proportional tax but collects no welfare.

E. A welfare recipient would want higher taxes. But certainly not 100%, because then no one would want to produce the goods the welfare recipient intends to consume.

F. Simple M&R story suggests you should be able to roughly slice the income distribution into two political factions: the rich and the poor.

G. What wins in equilibrium? There is positive redistribution as long as mean income exceeds median income.

H. They argue that their model explains the expansion of government. As the franchise expanded, so has the divergence between median voter income and mean voter income. Poorer voters, in their rational self-interest, request higher taxes and more redistribution when asked.

I. In M&R model, redistribution is not a product of special interest lobbying, economic confusion, or altruism.

J.

In spite of its Chicago

IV. Empirical Evidence on the SIVH

A.

There is an enormous literature on the SIVH in general, and

M&R-type thinking in particular.

B.

Many of these tests - particularly those performed by economists - rely

on aggregate data. Peltzman (1985) is a classic paper in

this tradition.

C.

Examples:

1.

Are poorer ethnicities more Democratic?

2.

Are richer Congressional districts more conservative?

3.

Do SS payments rise when a higher percentage of the elderly vote?

D. The results on these sorts of tests are mixed, and there is a lot of interpretive ad hocery.

1.

Ex: “Liberalism as a normal good”

E.

Tests on aggregate data do reveal something, but are clearly inferior

to tests that rely on data about individuals'

political beliefs and their personal characteristics (income, education, race,

age, etc.) relevant to self-interest.

1.

Political scientists pay far more attention to this sort of evidence.

F.

Amazing and important conclusion: the SIVH flops. You can find some sporadic and debatable

evidence for self-interested political beliefs, but that is about it.

G.

Consider the case of party identification. Conventional wisdom tells us that

"the poor" are Democrats and "the rich" are Republicans.

H.

In fact, the rich are only slightly more likely to be Republicans than

Democrats. (Factoids from the

SAEE).

1.

Race matters far more than income: High-income blacks are much more

likely to be Democrats than white minimum wage workers.

2.

Gender also dwarfs the effect of income: a man earning $25,000 per year

is about as likely to be a Democrat as a women earning $100,000 per year.

I.

The SIVH fails badly for individual issues as well.

1.

Unemployment policy - The unemployed not much more in favor of relief

measures.

2.

National health insurance - The rich and people in good health are

about as in favor.

3.

Busing - Childless whites are as opposed as whites with children.

4.

Crime - Crime victims and residents in dangerous neighborhoods are not

much more likely to favor severe anti-crime measures.

5.

Social Security and Medicare- The elderly are if anything slightly less

in favor than the young.

6.

Abortion - Men are slightly more pro-choice than women.

J.

The SIVH fails for government spending, but has some moderate support

for taxes.

1.

People expecting large tax savings from Proposition 13 were more likely

to support it.

2.

But recipients of government services and government employees were

about as likely to support Prop. 13 as anyone else.

K.

The SIVH fails for potential death in combat! Relatives and friends of military

personnel in

1.

Marginal evidence for SIVH - exact draft age.

L.

Best example of a strong self-interest effect: Smoking!

1.

Even though smokers and non-smokers are demographically similar,

non-smokers are much more in favor of restrictions on smoking.

2.

The heavier the smoker, the stronger the opposition.

3.

Only 13.9% of people who "never smoked" supported fewer

restrictions, compared to 61.5% of "heavy smokers."

M.

Overall, this body of evidence can only be described as

revolutionary. It is very hard to

argue against it, and it means that most of what people think and write about

politics is wrong. Thousands of

articles - and millions of conversations - have been a big waste of time

because no one bothered to examine the empirical evidence.

N.

Moreover, the empirical evidence is intuitively plausible. Are your richer friends really the

Republicans, and your poorer friends the Democrats? Can you find any connection at all? It isn't easy.

O.

Thus, tests of the Median Voter Hypothesis that assume voters are

self-interested are almost bound to fail.

Why? If voters are not

self-interested, then the failure of policy and the median voter's

self-interest to "match" proves nothing.

V.

Sociotropic Voting

A.

One major alternative to the SIVH, popular among many political

scientists, is called "sociotropic voting."

B.

Sociotropic voting means voting for policies that maximize "social

welfare" or something along those lines.

C.

Sociotropic voting is introspectively plausible and works in some

interesting empirical tests.

D.

Ex: Good economic conditions make politicians more popular. But what matters is mostly overall economic conditions, not those

of the individual respondent.

E.

But it does little to explain voter disagreement. If everyone wants to maximize

"social welfare," why don't they all vote the same way? In contrast, the SIVH has a ready

explanation for disagreement.

F.

What would the M&R model predict if voters were sociotropic? Taken literally, it predicts full

consensus.

1.

Where would the consensus lie?

It depends on the deadweight costs of taxation and welfare, the shape of

the utility function, initial endowments, etc.

VI.

Group-Interested Voting

A.

While the SIVH fails badly, there is strong evidence for group-interested voting.

B.

What's the difference? If a

policy hurts you but helps your "group," how do you vote and

think? If you go with the group,

your voting is group-interested, not self-interested.

C.

Ex: The black millionaire.

Democrats favor higher and more progressive taxes (which hurts the

millionaire a lot), but also care more about the plight of blacks (which does

virtually nothing for the millionaire; no one will discriminate against him). If self-interested, he would vote

Republican; if group-interested, he would vote Democratic.

D.

Much of the superficially plausible evidence for self-interested voting

turns out to be group-interested when you look more deeply.

E.

Ex: Jewish support for

F.

The income-party correlation is stronger in other countries than in the

1.

Interesting test to try: How many people would switch parties after

winning the Lottery?

G.

Group-interested voting gives a better theory of disagreement than

sociotropic voting. People vote

differently because the groups they belong to differ, and groups have divergent

interests.

H. Moreover, most people identify with more than one group, and to varying degrees. Classic example: Religious workers in countries with major anti-clerical socialist movements.

I. The group-interest model works in a lot of different countries and time periods. Defining the relevant groups provides some empirical “wiggle room,” but not that much.

VII. Case Study: The Determinants of Party Identification, I

A.

What happens if you use basic

econometrics on data from the General Social Survey to try to sort out the

determinants of party identification?

N≈49,000 for 1972-2010,

so focus on magnitudes, not t-stats.

B.

Linear

probability model:

Predict the probability of being a Democrat or being a Republican conditional

on your personal characteristics.

C.

What if you ignore ideology, and try to predict party identification

using only real income (in 1986 dollars), education (in years), race, sex

(1=male, 2=female), age, and year?

D.

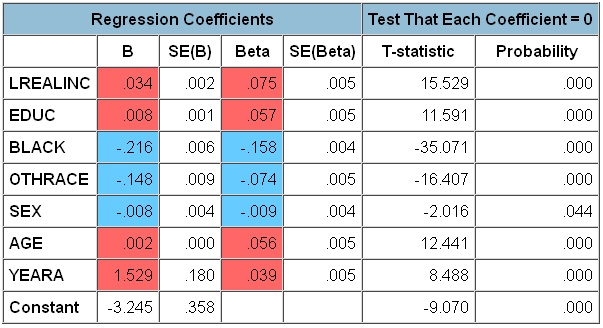

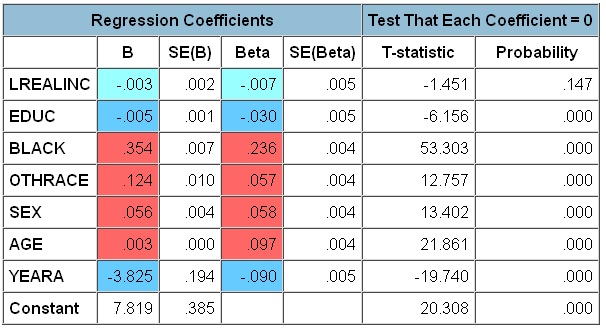

[Table 1a&1b]

1.

Income. Income matters in the expected direction

for Republicans, but the magnitudes is tiny. If real income rises by 10%, P(Rep)

rises by 0.34%.

2.

Education. A year of education makes people .8

percentage-point more Republican and .5 percentage-points less Democratic. (Remember this is all years)

3.

Race. Blacks are massively more likely to be

Democrats (+35 percentage-points) and less likely to be Republicans (-22

percentage-points). The same

pattern holds – albeit more moderately – for members of

“other races.”

4.

Gender. Females are markedly more likely to be

Democrats (5.6 percentage points).

5.

Age. Older people are a little more likely to

be both Democrats and

Republicans. (Remember independents

are the omitted category).

6.

Year/1000. The population has grown less Democratic

and more Republican over time.

E.

What does all this show?

1.

Strong evidence for group-interested voting, with race being the main

group of interest.

2.

Self-interest plays a marginal role at most.

VIII. Rejoinders

A. Most economists would strongly resist my empirical summary. Why?

B. Objection 1: Empirical measures of self-interest are highly imperfect. Why assume “the rich” and “the poor” have common interests in begin with?

C. Ex: Maybe black millionaires rely heavily on government contracts.

D. Objection 2: Incidence complicates matters further. In theory, progressive taxes might actually be paid by the poor.

E. Ex: Maybe regulation actually hurts the poor more than the rich.

F. How convincing are these objections? To my mind, not very. They cut both ways: If measurement error and policy incidence are that ambiguous, we shouldn’t take the studies confirming the SIVH seriously either.

G. Another example: The Kenny and Lott study of women’s suffrage.

H. Further complication: Magnitudes. Maybe Democrats are better for women, but does a male-female partisan gap equal to the $25k-$100k partisan gap make sense?

IX. Gelman on Income and Voting

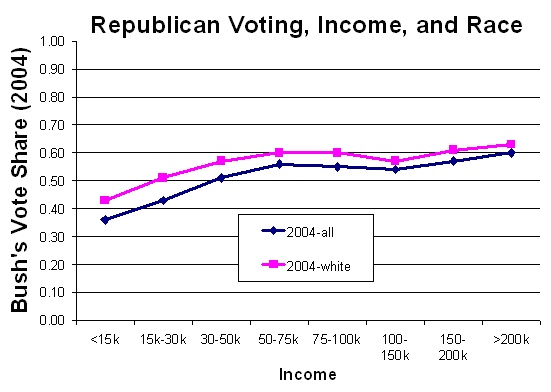

A. In Red State, Blue State, Rich State, Poor State, Andrew Gelman seems to argue in favor of a sophisticated version of the SIVH.

B. At the state level, the correlation between Democratic vote share and income is actually positive.

C. But this is only aggregate data. When you look at individual data, higher income predicts more Republican voting.

D. This effect gets stronger if you look at the data state-by-state. States change the intercept and the slope, but the slope almost always has the sign predicted by the SIVH. “Income matters, but so does geography.”

E. The slope is steeper in lower-income states. In CT, it’s almost flat.

F. But how much do these results really support the SIVH? The findings on state effects support a group-interest story. Furthermore, Gelman admits that about half of the effect of income goes away if you omit black voters from the analysis – further evidence of group-interest effects.

G. Furthermore, in absolute terms the slope Gelman finds for income is small. For white voters, Republican voting is perfectly flat for incomes from 30k to 150k – you can quintuple income without changing a thing.

H. Note further that the brackets do not contain equal fractions of the population! The appearance of a pattern largely stems from the 8% of voters with incomes under 15k, and the 3% with incomes over 200k.

X.

The SIVH Versus the Logic of Collective Action

A.

How is all this unselfish voting possible? It seems to conflict with the logic of

collective action - people sacrifice their own political interests without hope

of compensation.

B.

But this impression is misleading.

Why? Precisely because one

vote is extraordinarily unlikely to change an electoral outcome, it is very

safe to vote against your own interests!

C.

Ex: When Barbara Streisand

votes for a candidate that will charge her $2 M more in taxes, is that

equivalent to giving $2 M to charity?

D.

Of course not. Her vote

won't change the election's outcome.

If the Democrat wins, she has to pay, but he would have won - and she would have to pay - anyway! So the MC of voting Democratic is not $2

M, but $2 M times the probability that she casts the decisive vote. Even if that were a high 1-in-2 M, her

expected cost of voting Democratic would only be $1.00.

E.

The logic of collective action cuts two ways. It makes people unwilling to contribute

serious effort for political change.

But it also makes people unafraid of voting contrary to their own

interests.

Table 1a: Conditional

Probability of Being a Democrat

Table 1b: Conditional

Probability of Being a Republican