The Russian Civil War and the Russo-Polish War

The Bolsheviks soon moved their capital from Petrograd to Moscow, surrounding themselves with bodyguards. They knew that their policies were sure to alienate much of the population. Those who hated Lenin's regime scanned the political landscape for a savior. But no savior was available, only several desperate and vaguely monarchist "White" armies. Once again, Lenin's disciplined vanguard party proved itself able to defeat its confused and divided opponents, in a sequence of bloody battles known as the Russian Civil War.

The first opponents of Lenin's regime to take up arms were the Cossacks in

the south of Russia. While their will to fight the Bolsheviks was great,

they had a fatal weakness, as Landauer explains: "Although the Cossacks

were dangerous enemies because of their highly developed military qualities,

in political matters their scope was utterly limited. They had no common

goal except the defense of their property and they failed to understand

that the success of this defense depended on the annihilation of the

Soviet regime in all Russia, and not merely on local victories."

(European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements) A string

of would-be supreme generals tried to bring the Cossacks and other anti-

Bolshevik forces in southern Russia under a common banner. The first was

General Michael Alexeyev, Kerensky's former chief of staff. Due to illness,

Alexeyev was soon replaced by General Kornilov. Kornilov led the so-called

White forces for a couple of months, but had the bad luck to die in battle.

One General Anton Denikin assumed command of the Cossack forces, in an

uneasy alliance with the pro-German General Krasnov.

The first opponents of Lenin's regime to take up arms were the Cossacks in

the south of Russia. While their will to fight the Bolsheviks was great,

they had a fatal weakness, as Landauer explains: "Although the Cossacks

were dangerous enemies because of their highly developed military qualities,

in political matters their scope was utterly limited. They had no common

goal except the defense of their property and they failed to understand

that the success of this defense depended on the annihilation of the

Soviet regime in all Russia, and not merely on local victories."

(European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements) A string

of would-be supreme generals tried to bring the Cossacks and other anti-

Bolshevik forces in southern Russia under a common banner. The first was

General Michael Alexeyev, Kerensky's former chief of staff. Due to illness,

Alexeyev was soon replaced by General Kornilov. Kornilov led the so-called

White forces for a couple of months, but had the bad luck to die in battle.

One General Anton Denikin assumed command of the Cossack forces, in an

uneasy alliance with the pro-German General Krasnov.

The Denikin and Krasnov forces were no significant threat to Lenin's regime

until the summer of 1918, when Trotsky provoked a bizarre international

incident. A large army of Czech prisoners of war had been permitted by

Kerensky's government to form units to fight the Central Powers. The plan

was to transport the new Czech army by railroad across Siberia to the

Pacific Ocean, and then sail them to France.

Although the Czech units were

in fact friendly to the Bolshevik cause, Trotsky strangely decided to

halt the rail progress of the Czech army and instead ordered the Czechs to

"join the Red Army to be pressed into 'labor battalions' - that is, become

part of the Bolshevik compulsory labor force. Those who disobeyed were to

be confined to concentration camps." (Richard Pipes, The Russian

Revolution) The Czechs resisted with force, seizing much of the rail

system and emboldening the scattered Russian anti-Communists. Amidst this

disorder, the Bolsheviks former allies, the Left SRs failed at an attempt

to seize power.

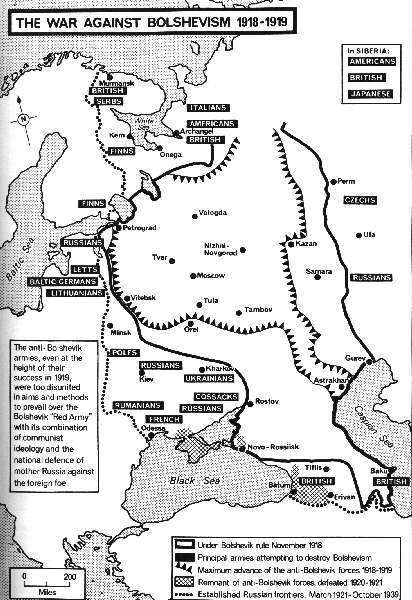

Around this time token Allied forces arrived in the

Arctic port cities of Murmansk and Archangel, while more substantial

Japanese forces moved to occupy Russia's Pacific coast. (As mentioned

earlier, Allied intervention has been seriously misrepresented in many

accounts of the Russian Civil War - for details, see the Museum's

Special Exhibit on the topic).

Although the Czech units were

in fact friendly to the Bolshevik cause, Trotsky strangely decided to

halt the rail progress of the Czech army and instead ordered the Czechs to

"join the Red Army to be pressed into 'labor battalions' - that is, become

part of the Bolshevik compulsory labor force. Those who disobeyed were to

be confined to concentration camps." (Richard Pipes, The Russian

Revolution) The Czechs resisted with force, seizing much of the rail

system and emboldening the scattered Russian anti-Communists. Amidst this

disorder, the Bolsheviks former allies, the Left SRs failed at an attempt

to seize power.

Around this time token Allied forces arrived in the

Arctic port cities of Murmansk and Archangel, while more substantial

Japanese forces moved to occupy Russia's Pacific coast. (As mentioned

earlier, Allied intervention has been seriously misrepresented in many

accounts of the Russian Civil War - for details, see the Museum's

Special Exhibit on the topic).

Amidst this flurry, Trotsky forged the Red Army out of peasant conscripts, long-time Bolsheviks, and sympathetic ex-Czarist officers. With assistance from the Czechs, anti-Bolshevik forces captured Kazan and Samara (see map). A September, 1917 conference in Ufa tried to unify anti-Bolshevik forces in Siberia, but within two months one faction had arrested the other and control fell to one Admiral Kolchak. With this move the Kolchak forces alienated the Czechs and provoked anti-Bolshevik SRs to declare a two-front struggle against Reds and Whites alike. Meanwhile the Japanese threw their support to the Ataman Gregor Semenov, who operated a yet another anti-Bolshevik government around Vladivostok, while the Anarchist armies of Nestor Makhno fought Reds and Whites alike throughout the Ukraine.

An army cannot be built without reprisals. Masses of men cannot be

led to death unless the army command has the death penalty in its arsenal.

So long as those malicious tailless apes that are so proud of their

technical achievements - the animals that we call men - will build armies

and wage wars, the command will always be obliged to place the soldiers

between the possible death in the front and the probable one in the rear.

|

By now White forces everywhere were in retreat. Denikin's army was beaten back all of the way to the Crimea. Increasingly unpopular, Denikin resigned his command in favor of General Peter Wrangel. Kolchak's forces suffered severe defeats, and the Czech decision to evacuate (and hand Kolchak over to SRs for execution). The war seemed to be essentially at its conclusion. But the outbreak of war between Lenin's regime and the new nation of Poland gave the Whites one last hope.

Initially Polish successes were very impressive. Minsk and Kiev fell to Poland's armies. Misled by this turn of events, Wrangel's armies in the Crimea made a final offensive northwards. But the Red Army decisive beat back the Poles and drove into the heart of Poland. Now that their enemies had been beaten back, the Red Army began what Franz Borkenau called "the attempt to carry revolution into the West with Russian bayonets." As Borkenau elaborates:

Trotsky, in the gazette of his armoured train, wrote an article in which he claimed to see the Red Army, after defeating the Whites, conquer Europe and attack America. And Sinovjev, in number 1 of the Communist International, prophesied that within a year not only would all of Europe be a Soviet republic, but would already be forgetting that there had ever been a fight for it. (Franz Borkenau, World Communism)

One year later, the second meeting of the Comintern coincided with the Red Army's offensive into Poland. Zinoviev addressed the conference, and joked about his overly optimistic prediction:

"[P]erhaps we have been carried away; probably, in reality, it will need not one year but two or three years before all Europe is one Soviet republic. If you are so modest that one or two years' delay seems to you extraordinary bliss, we can only congratulate you for your moderation." (quoted in Franz Borkenau, World Communism)

Representatives of the Polish Communist Party, slightly more informed of real conditions in Poland, voiced the concern that the Polish proletariat was unlikely to take up arms to aid the Red Army's invasion. Trotsky too had doubts, but Lenin urged on the attack. Many attribute the failure of this invasion to the refusal of Joseph Stalin to cooperate with Tukachevsky. In any case, the Poles routed the Red Army in what has been often called "the Miracle of the Vistula." A Russo-Polish treaty soon followed, leaving the Red Army to mop up the remnants of their opponents. Baron Wrangel's forces were beaten back and evacuated from the Crimea.

Allied forces had long since abandoned their positions, but Japanese forces

remained in along Russia's Pacific coast. In April, 1920 the Bolshevik

Alexander Krasnoshchekov declared the establishment of an "independent"

Far Eastern Republic based in Chita and claiming sovereignty over territory

occupied by Japan. While Krasnoshchekov

was plainly a Leninist puppet, he purported independence won the support

of many wavering factions who might have resisted a frankly Communist

regime. Japan withdrew from Vladivostok in late 1922; soon afterwards,

the Red Army (not the army of the Far Eastern Republic) took Vladivostok.

Four weeks later the Far Eastern Republic puppet voted to unite with the

rest of Soviet Russia.

As Landauer observes, "[T]he Bolsheviks knew only

too well how valuable the relative freedom of Finland had been to Russian

revolutionaries under the tsarist regime. Lenin and Trotsky were not

willing to run the risk of letting opponents find a refuge in Eastern

Siberia; hence that country was ruled by the same relentless methods which

were used against all dissenters from communism in the rest of the Soviet

Republic..." (European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements)

As Landauer observes, "[T]he Bolsheviks knew only

too well how valuable the relative freedom of Finland had been to Russian

revolutionaries under the tsarist regime. Lenin and Trotsky were not

willing to run the risk of letting opponents find a refuge in Eastern

Siberia; hence that country was ruled by the same relentless methods which

were used against all dissenters from communism in the rest of the Soviet

Republic..." (European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements)

As in most wars, the behavior and intentions of the various factions in the Russian Civil War ranged from bad to worse. The Whites have justly earned infamy for their anti-Jewish pogroms, mass executions of POWs, and innumerable other atrocities. But it should be pointed out that in most cases the Whites' brutality was rarely ordered from Denikin or Kolchak as official policy, but was instead largely the result of lower-level officers' initiatives. In contrast, the Communists' inhumanity was publicly ordered by the highest levels of Lenin's government. As Carl Landauer astutely points out:

Unlike their opponents, the Bolsheviks needed not only power to carry out the terror but also the arguments to defend it ideologically... One cannot imagine a White general writing an apology of terrorism in his spare time. Trotsky, in the midst of battles, wrote his booklet The Defence of Terrorism as a reply to Kautsky's attack upon Bolshevik methods. What would have been a waste of energy for one party was a necessity for the other...(European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements)

The war crimes of the Bolsheviks were numerous, and not nearly as well publicized as those of the Whites. Just as the Whites massacred large numbers of Jews, the Bolsheviks (apparently under Lenin's orders - see the documents in Richard Pipes The Unknown Lenin) were guilty of the mass extermination of the entire Don Cossack people - killing an estimated 700,000 out of around 1,000,000 of them. (This would prove to be only the first of several near-genocides of ethnic minorities within the Soviet Union). The Red Army showed especial brutality to surrendering Whites and civilians sympathetic to them. (Kolchak's armies and associated civilians suffered particularly awful treatment because the Allies made no effort to evacuate these refugees before departing, as they did with the Whites in the Crimea). In the train of the army followed the Cheka, eager to apply more systematic penalties for opposition to the Soviet state.

|

| ||

| ||

|

|